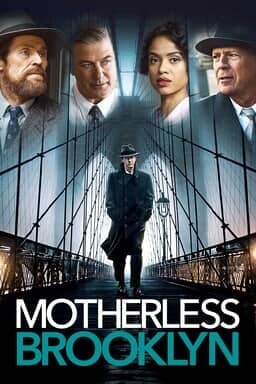

I recently watched “Motherless Brooklyn” and

“Richard Jewell” which are both hot off the red box and they are a stark

reminder of the way two films can hint at the ideologies of their makers and my

evolution in reading them.

“Motherless Brooklyn” stands out primarily

as a great film and showcase for Edward Norton who co-adapted the book and

directed in addition to playing a starring role. Stylistically, the film takes

its cues from film noir with a detective falling deeper and deeper into a well

of obsession and that’s not an easy genre to re-capture, let alone put a spin

on. On top of that, it’s a little “Chinatown” meets “Rain Man” as Norton’s

character has tourette’s syndrome which takes guts: Imagine the potential this

has to be disastrous both to film noir and the disabled community if handled

sloppily.

Like one of the great neo-noirs,

“Chinatown”, (the vast majority of noirs came out in the 40s and 50s and

“Chinatown” was in the 70s, “Motherless Brooklyn” seeks to make infrastructure

sexy. “Chinatown” explores how the city of Los Angeles was built through

irrigation systems. “Motherless Brooklyn” derives from the story of Robert

Moses who cut through a tremendous amount of red tape and created a series of

bridges and highways that some say modernized New York and allowed connectivity

between the five boroughs at an unprecedented level.

At the same time, Moses wasn’t without his

flaws: He bulldozed neighborhoods for urban-renewal projects and designed the

highways on Long Island so that buses couldn’t travel. For those who are look

at society and policy through the lens of racist verse not racist and want to

disregard all the shades of blue in the middle, this makes him target for a

certain negative revisionist history that’s becoming popular (even though

classist doesn’t necessarily mean racist and a man’s views are a product of his

time to some degree). Decisions to not build certain highways that could

benefit poorer populations are now being characterized as racist because of the

interchangeability of class and race.

Nonetheless, while there is room for

critique about whether Moses or his policies were abnormally racist, as CityLab

has artfully done, “Motherless Brooklyn” chooses to eliminate any nuance in

the argument. By my tastes, it’s narrowly within the realm of artistic license,

but the whole movie can definitely be classified as woke. The film has a black

woman as a love interest for the character and celebrates intersectionality by

suggesting the black community and disabled as fitting allies for one another.

Additionally, the film’s moral universe might be seen as giving a bigger moral pass

to the vices of the black community than the community to which Lionel comes

from.

I generally argue that film makers have the

right to tell the kind of story they want without getting politically skewered,

so even if the film preaches a more woke philosophy than I generally subscribe

to, I’m comfortable with the film though cautiously aware of its slant when

comparing it to the real-life figures and times it is portraying.

The larger question, however, is whether “Motherless Brooklyn” exists in a vacuum.

If this didn’t exist alongside the Ava DuVernays and Spike Lees that see their

mission as filmmakers to be synonymous with their activist views, I might be

more ok with the film’s lean. Alternatively, the sphere of film critics out

there lean heavily liberal and will take such messages about Robert Moses and

use this film to write insufferable and likely factually incorrect essays.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have film maker Clint Eastwood who is a popular

figurehead for conservatism (especially around the time of the McCain

and Romney campaigns). His film “Richard

Jewell” centers around the true story about a man who was accused of the

Atlanta bombing he didn’t commit. Because the man was a cop and the FBI tries

to latch onto the same aggressive tendencies any cop might have, the film aligns

pretty heavily with the blue lives matter. The film’s implication (based pretty

heavily on the facts)

also is that Jewell was targeted because he was fat and ungainly so it also

doubles as a weird kind of body-shaming PSA.

And here’s the odd thing: I’m not a conservative

at all and I’d like to think my contempt for the current leadership of that

party is well-documented. But in the cultural sphere? I’ve had a shift (also

well-documented) and from where I’m standing it looks the more conservative of

these two films is a more compassionate portrait of a historical event. Why?

Eastwood’s film is about reconsidering preconceived notions towards a fairer

view of reality. In contrast, “Motherless Brooklyn” is about finding comfort in

sticking its protagonist (and audience) between familiar notions of good and

evil even if they’re not particularly accurate. I never thought I’d live to see

the day when I liked the film with the more conservative slant but there it is.

No comments:

Post a Comment